In the emerging frenzy of the 2024 GOP primary election, entrepreneur and author Vivek Ramaswamy has managed to pierce the public consciousness. Following the first primary debate, his resulting spike in the polls has made him competitive for second place - albeit in a race that remains largely in the shadow of Donald Trump. Ramaswamy is remarkable for several reasons: he is the first millennial candidate on the GOP side to pursue the presidency; he is a political outsider with a background that mixes law, science, and business; and while he is not the first Indian-American candidate we’ve had, he is the first that has stalwartly affirmed his Hindu faith.

The interesting question, though, is what exactly does Vivek mean when he says that he believes in “One God”? While I can’t claim to know the authentic particulars of his religious convictions, I do think that that several of his public statements on the topic have provided enough data to reasonably triangulate where in the diverse tapestry of Hindu beliefs his own convictions might lie.

In a recent town hall, Vivek was directly asked about his religious beliefs by a member of the audience. Before explaining on his own specific beliefs, he states that Hinduism, like other faiths, has many strains of thought - drawing a comparison to the seemingly analogous diversity seen across Christian sects. He then asserts that he believes in “One True God”, and believes that this God resides in all of us. In his elaboration, he distinguishes this belief from the Christian belief that we are made in God’s image, and that Jesus Christ is the only begotten Son of God. Interestingly though, he says that he views Christ as a son of God, and intimates that the “spirit” of God in both the Christian and Hindu contexts converge on a universal divinity.

In a subsequent interview, Vivek defends against the (implicit) claim that he believes in multiple gods, citing again the diversity in Hindu traditions. He then broadens the conversation into one of moral value, echoing the sentiment that he routinely tries to express across his stump speeches and campaign events. In his estimation, there are shared principles and values between the Christian teachings that he was exposed to in Catholic school and the Hindu faith that he practices. All of these public encounters invite a natural question: what form of Hinduism is Vivek referring to?

Divine Diversity

As examined in prior posts, Hinduism consists of a wide tapestry of interconnected philosophies, rituals, and mythologies. While there are six overarching “orthodox” schools of belief, the current reality has emerged out of four thousand years of sprawling theological development across an entire subcontinent. Members of a single Hindu family, ostensibly all part of a common tradition, will often participate together in rituals while holding different beliefs about the divine. Remarkably, despite the sprawling diversity, Hinduism has managed to maintain a common core that holds reverence for a foundational set of liturgical texts (The Vedas), and generally promotes a tolerance for diverging views on particular gods, rituals, and metaphysics.

If we consider a compound statement that encapsulates Vivek’s repeated comments about his Hindu faith - that there is One True God, who resides within all of us - it gives us a reasonable place to begin our inquiry. Somewhat counterintuitively, the part about him believing in a singular, identifiable God doesn’t really narrow things down. Five of the six overarching schools leave room for believing in a pantheon of different gods, in a henotheistic structure that places one god as primary among others, or in a singular God that subsumes all other divine representations in some fashion. Rather, the operative part of Vivek’s stated beliefs is the claim that the singular God exists within each of us.

Vedanta is the school of Hinduism that firmly asserts a singular and undifferentiated Godhead, usually identified by the Sanskrit word Brahman. The Advaita school of Vedanta draws exactingly monistic conclusions about the nature of Brahman, claiming that the Godhead and all of creation ultimately consist of the same divine substance. In the Advaita system, spiritual liberation (moksha) is the result of piercing through the illusion of separation between yourself and rest of reality. This belief is in contrast with the Dvaita system, which believes there is real distinction between the individual human soul, various elements of the material world, and the Godhead. Dvaita is perhaps the closest to Christian metaphysics of all of the Vedantic schools, claiming that individual human souls and the material world are categorically distinct from the omnipotent God that created them.

Given that Vivek believes that a singular God is capable of residing within each of us, it seems logical to conclude that he adheres to some form of Advaita Vedanta. Moreover, his family’s origins trace back to a city in the South Indian state of Kerala, which has a longstanding and noteworthy Advaita community. I have not seen firm confirmation that Vivek is indeed a member of the Palakkad Iyers, but it is a reasonable conjecture given his surname and beliefs. (Wikipedia and Reddit both seem convinced, for whatever that’s worth.)

Before we consider the case closed, it is worth considering a third school of Vedanta that almost functions as a midpoint between the Advaita and Dvaita schools, known as the Vishishtadvaita school. It puts forth a form of qualified monism, that recognizes that God (Brahman) is singular and pervades all of reality, while simultaneously acknowledging distinctions between God in absolute form, God within individual souls, and God within material reality. At the crux of the system’s nuanced metaphysics, there is a core belief that constant transformation is an essential part of God’s nature - and therefore the resulting differences must be recognized. This distinguishes Vishishtadvaita from the unqualified monism of Advaita.

Practical Principles

If we assume that Vivek adheres to some form of monistic Vedanta, whether qualified or unqualified, it anchors his claims about a singular God that permeates all of us (and all of reality, for the matter). Of course, many voters are concerned about what these underlying metaphysical positions practically entail, when placed in the context of a candidate’s character and code of ethics. Vivek has consistently framed his own Hindu values as being in harmony with those taught in Christianity - an appeal that is of obvious importance, in the overwhelmingly Christian GOP.

Hindu ethics, like the rest of the religion, is a complex web that manifests in different ways across different traditions. The concept of dharma, or divine duty, is inherently contextual - and the major Indian stories are full of situations where “easy” morality is put to the test, against the backdrop of a greater outcome. Some traditions provide broad frameworks that define one’s dharma based on birth or cosmology; while others consider all duties to be ultimately transient, apart from the imperative to achieve spiritual liberation. Karma has taken on many pop-culture renditions in the West, and simply translates to “action” in Sanskrit. It is a category of consideration, more than a discrete concept; it can pertain to daily conduct, the cause-and-effect that ripples through the material world, and cosmic continuity that flows along with the soul (which, as you might have surmised, can mean very different things - depending on the underlying philosophical tradition).

That being said, there are common moral axioms that are found in virtually all strains of Hinduism, which are rooted in The Vedas themselves. The Rigveda - widely considered the oldest text in Indo-European history - puts forth five moral refrains (yamas): non-violence (ahimsa), control over sexual impulses (brahmacharya), refrain from stealing (asteya), refrain from lying (satya), and non-attachment to worldly possessions (aparigraha). It would be exceedingly difficult to find a Hindu tradition today that would deny the five yamas. As Indian moral philosophy developed in the Post-Vedic period, a set of positive precepts called niyamas (i.e., the do’s, which complement the don’ts given by the yamas) emerged across both Hinduism and Buddhism. A famous set of niyamas can be seen in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras: maintaining purity and clearness of mind (shaucha), exercising self-discipline and regular meditation (tapas), exercising tolerance and acceptance of all others (santosha) - to name a few.

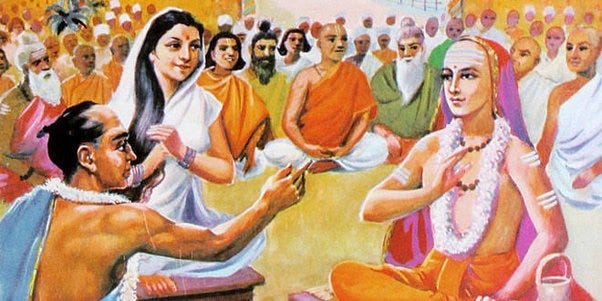

If Vivek wins the presidency, it’s likely he will place his hand on a copy of the Bhagavad Gita, as he takes the oath of office. The Gita is the most recognizable Hindu text in the world; it describes the teachings of Krishna (an incarnation of Vishnu, often considered the preserving aspect of Brahman) given to the warrior-prince Arjuna - and details the nature of reality, and the contextual imperatives found in one’s personal dharma and karma. The morality expressed is complex, with the story literally taking place on a battlefield. Many parts of the text resolutely reinforce the aforementioned yamas and niyamas; the bedrock of proper conduct, as Krishna articulates it, would not surprise Western readers. The complexity arises in the particular navigation of the war, and Krishna’s affirmation to Arjuna that despite his heartache, he must fight and win the battle against his cousins’ army. Critics of the Gita are quick to point to a narrative ambiguity that provides no clear-cut morality; while defenders maintain that the whole point is to show the inherent complexity in navigating timeless principles, the interlocking duties to one’s family and community, and larger notions of cosmic justice.

Bridging Beliefs

When considering the conventional elements of Hindu morality, we can see where Vivek is drawing from when he makes universalist appeals. When he speaks of believing in One God, he is likely speaking of an all-pervading Godhead that governs the entire universe, is the prime mover behind all activity in the material world, and is the ultimate contingent reality upon which our individual souls rest. When he speaks of the primacy of family, truth-telling, and respect for others - he is drawing directly from the principles outlined in The Vedas, and a large fabric of subsequent theological writings. The deeper he ventures into the religious underpinnings of discipline and duty, the more we that hear echoes of Krishna’s teachings in the Gita. Out of the seemingly endless nuance that exists across the different Hindu schools, Vivek has been able to channel a consistent and legible spiritual language.

It remains to be seen whether Christian voters will accept Vivek’s overtures, given the legitimate and meaningful distinctions that exist between the faiths. Yes, a Hindu framework can acknowledge the divinity of Jesus Christ - and can even exalt him as an incarnation of the One True God; but this is not precisely the same as what is proclaimed in the Nicene Creed. To Vivek’s credit, he does not attempt to blur these distinctions; in rooms full of conservative voters, across a nation that still finds most Hindu beliefs inscrutable, he respectfully and repeatedly clarifies that he views Jesus Christ as a son of God, rather than the Son of God. Moreover, he answers these kinds of questions with the energy of a happy warrior - eager to speak to a commonality in values, rather than collapsing the two faiths into a generic moral soup.

Regardless of what one might think of his policy proposals or other doings, it’s hard to argue that Vivek’s approach to sharing his faith has been anything other than admirable, and quintessentially American.

Great explanation, thanks!