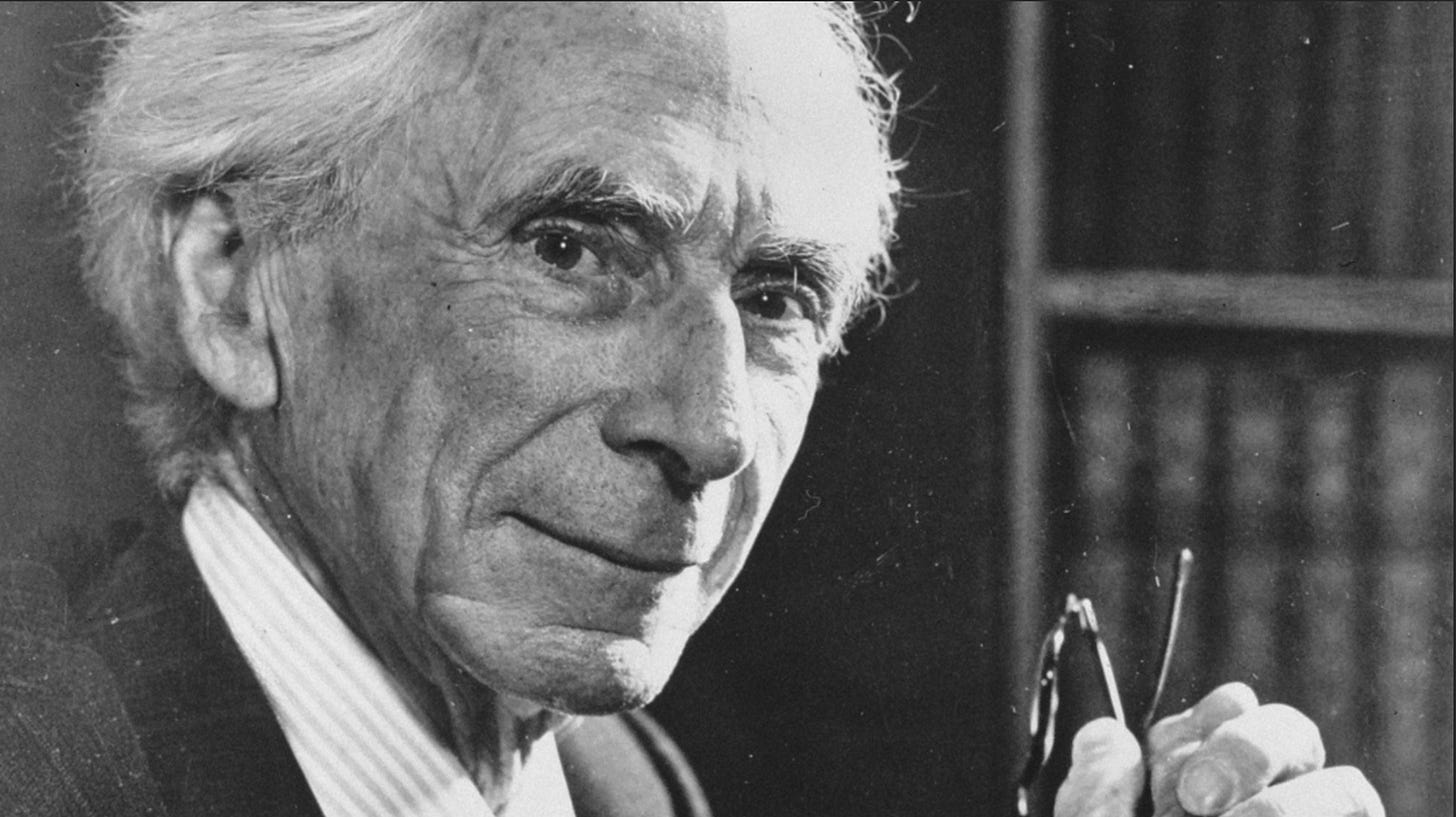

Bertrand Russell’s legendary compendium, A History of Western Philosophy, took me almost a year to complete. I attribute that mostly to my atrophied reading muscle, rather than any qualities of the book (though it is nearly 800 pages). I wanted a “reasonable summary” of European philosophy before diving into particular thinkers, and Russell’s writing delivered.

The first third of the book is devoted to the philosophies of Ancient Greece. Russell takes a few chapters to paint a sociocultural picture of the Hellenic world - religion, war, influences from neighboring civilizations - before digging into specific schools and individuals. He starts with the the Pre-Socratic schools, which I knew little about. The Milesian School featured characters like Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes - who all had their own, firmly-held convictions about the true substrate of reality (was it air? something ethereal? water?)

Russell’s lens into Pythagoras is particularly amusing. We all think about the man’s contribution to mathematics…but what about his extreme opinions on food (e.g., don’t eat beans because they’ll give you gas, which will cause you to expel your life energy), the way he enmeshed his teachings with a supernatural cult, and his supposed ability to calm the seas and talk to animals? He’s a complex figure that Russell does justice:

“But in Plato, Saint Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Descartes, Spinoza, and Kant there is an intimate blending of religion and reasoning, of moral aspiration with logical admiration of what is timeless, which comes from Pythagoras…”

The first book then continues on through focused summaries of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Russell does a nice job providing clear renditions of their core teachings, while providing his own (clearly delineated) analysis. His critiques are usually fair, and often written with a bit of whimsy. These three thinkers have always been difficult for me to read, even in snippets; much of what they say seems very “logical” to modern eyes; it’s only in extended exposition, in conjunction with proper context, that their foundational value shines.

A brief section on Post-Aristotelian thinking and the Roman world bookends the first tome. Throughout the sections on the ancient world, Russell does a nice job foreshadowing what’s to come:

“The close connection between virtue and knowledge is characteristic of Socrates and Plato. To some degree, it exists in all Greek thought, as opposed to that of Christianity. In Christian ethics, a pure heart is the essential, and is at least as likely to be found among the ignorant as among the learned. This difference between Greek and Christian ethics has persisted down to the present day.”

The second book focuses on Catholic Philosophy. Russell once again provides great historical context, starting with the Judaic theological framework that was preserved by the legendary Hasidim. (Seriously, look up the story of Judah “The Hammer” Maccabee if you aren’t familiar with it 🔨) It becomes clear that the breadth of Christianity’s impact, apart from its core teachings, was in its ability to serve as a bridge between the Judaic and Western worlds. I hadn’t realized how precarious the faith’s early history was; its survival and progression was guaranteed by a handful of pivotal figures - Paul, Constantine, and the early Church Fathers.

As I read through the chapters on the Church Fathers, the word that stuck in my mind was hustle. Saints Jerome, Ambrose, and Augustine were seemingly tireless, debating doctrine and ironing out heresies throughout the Roman world with peripatetic zeal. Jerome painstakingly assembled the first Latin bible; Ambrose adroitly squashed rogue Christian offshoots that contradicted Catholic interpretation, solidifying the rigor of the Church and its relationship to the State. It is Augustine, however, who is considered the theological powerhouse (and even today, only Thomas Aquinas draws comparison). Russell, a harsh critic of Christianity throughout his life, clearly admired Augustine’s abilities - and left me curious to learn more about the Church Father:

“ Saint Augustine supplied the Western Church with the theoretical justification of its policy. The Jewish State, in the legendary time of the Judges, and in the historical period after the return from the Babylonian captivity, had been a theocracy; the Christian State should imitate it in this respect.”

“Saint Augustine is in some ways similar to Tolstoy, to whom, however, he is superior in intellect.”

The second book then glides through the rest of the first millennium, describing the fracturing of the Roman empire, the formalization and growth of the Papal system, and the stories of prominent Christian philosophers - including Saint Benedict and Gregory the Great. The interplay of Church and State fragments, drifts, and eventually gives rise to the Holy Roman Empire - which I remember learning in AP European History was neither Holy nor Roman. Russell details the bargain that Pope Leo III makes when he crowns Charlemagne the first Holy Roman Emperor; the Germans and Franks (previously regarded as barbarians) were legitimized, and made to be in communion with the theretofore exclusively Roman Church.

After tracing through the reign and collapse of Holy Roman Empire and the rise of the traditional nation-states, Russell discusses the Aristotelian syntheses of Thomas Aquinas and the Franciscan scholasticism, and then briskly outlines the transition between the eventual “eclipse of the Papacy” and the “Modern” era of philosophy.

“The period of history which is commonly called ‘modern’ has a mental outlook which differs from that of the medieval period in many ways. Of these, two are the most important: the diminishing authority of the Church, and the increasing authority of science.”

Starting with the Italian Renaissance, Russell describes the consequences of an increasingly corrupt Church that presided over an increasingly fragmented realm. The Reformation triggered by Luther severed the long-lived link between large parts of Western Europe and Papal authority, opening the doors to intellectual autonomy and a lot of bloodshed. Russell asserts that the foundations of religious tolerance, necessary for true diversity in science and philosophy, stemmed from gradual weariness with the wars of religion that ended up dominating the early 17th century.

The third book zips through the major figures of science (Galileo, Newton, Bacon..), setting the stage for Descartes - widely considered the founder of modern Western philosophy. Subsequent chapters on Spinoza and Leibniz show the development of complex, reason-centric systems of philosophy that drift progressively further from a dogmatic conception of the divine. The liberalization of the late 17th century paves the way for John Locke, and doctrines of liberty checking autocratic powers, and the formalization of empirical critique taken forward by figures like Berkeley and Hume.

“Hume’s philosophy, whether true or false, represents the bankruptcy of eighteenth-century reasonableness. He starts out, like Locke, with the intention of being sensible and empirical, taking nothing on trust, but seeking whatever instruction is to be obtained from experience and observation. But having a better intellect than Locke’s, a greater acuteness in analysis, and a smaller capacity for accepting comfortable inconsistencies, he arrives at the disastrous conclusion that from experience and observation nothing is to be learnt.”

Russell then moves into the romantic response to empiricism, spearheaded by the legendary Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Romanticism is described as a revolt against the interpersonal bonds that had been building into then-modern philosophy; it aimed at liberating the individual from social convention and social morality. Rousseau was a wildly colorful figure, and no snippets can really do him justice. He was constantly on the move throughout Europe - writing, indulging, provoking, and getting chased out of town; he’s said to have left his five children born out of wedlock at a Parisian orphanage; he was in deep poverty at the end of his life, and its suspected he committed suicide. Of all the characters in the book that jump off the page, Rousseau ranks alongside Pythagoras at the top of the list ; I need to learn more.

“Revolt of solitary instincts against social bonds is the key to the philosophy, the politics, and the sentiments, not only of what is commonly called the romantic movement, but of its progeny down to the present day.”

“At the present time [early 1940s], Hitler is an outcome of Rousseau; Roosevelt and Churchill, of Locke.”

The Modern Era then transitions into the mainstays of 18th century German Idealism (e.g., Kant, Hegel) and its contemporaries (e.g.,Schopenhauer). I’ve seen reviews of Russell’s book criticize this section in particular; while he clearly understands the construction of each thinker’s arguments, some contend that he’s selective in what he’s presenting (and subsequently critiquing). I haven’t yet read enough of the actual works to know whether this is true; but I did feel that this was the hardest section to digest. There’s a lot of domain-specific terminology, derivations, and relationships enmeshed in each thinker’s writings - which doesn’t lend itself well to being summarized in a compendium like this.

The final section of the book provides an overview of key 19th century philosophers (Nietzsche, Mill, Marx), before concluding with a look at the pragmatic philosophy of William James and John Dewey. Russell gives Nietzsche his due, drawing clear parallels between his “classical” (i.e., prideful, aggressive, artful) worldview and figures in the Renaissance:

“It is undeniable that Nietzsche has had a great influence, not among technical philosophers, but among people of literary and artistic culture. It must also be conceded that his prophecies as to the future have, so far, proved more nearly right than those of liberals or Socialists.”

“Nevertheless there is a great deal in him that must be dismissed as merely megalomaniac.”

Russell quickly dismisses the utility of Utilitarianism, while considering it a foundational slab in the then-emerging theories of Socialism - which would be made properly rigorous by Karl Marx. Marx is described as the last of the great German “system builders” - who attempted to provide a rational formula that summarized the evolution of mankind. Russell touches on the pillars of Marxist thought, such as dialectical materialism - but with same cursory touch as he does with the German Idealists, leaving me again with the feeling that I need to go properly read up.

“We may say, in a broad way, that Greek philosophy down to Aristotle expresses the mentality appropriate to the City State; that Stoicism is appropriate to a cosmopolitan despotism; that scholastic philosophy is an intellectual expression of the Church as an organization; that philosophy since Descartes, or at any rate since Locke, tends to embody the prejudices of the commercial middle class; and that Marxism and Fascism are philosophies appropriate to the modern industrial State.”

The final chapters on Pragmatism features a complimentary look at William James, who is affirmed as being among the greatest American philosophers (who also happened to be the most important American psychologist in history). Russell knew James personally, and mentions that his arguments on the need to radically reconsider the arbitrary distinction between mind and matter had convinced Russell to change his mind. He then proceeds to provide more targeted criticisms of the alternate system that James, in Russell’s estimation, fails to make clear. In John Dewey’s reframing of individual human experience within a broader organic community, Russell sees a reaction to the unrelenting scientific and social changes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries:

“Throughout this book, I have sought, where possible, to connect philosophies with the social environment of the philosophers concerned. It has seemed to me that the belief in human power, and the unwillingness to admit “stubborn facts,” were connected with the hopefulness engendered by machine production and the scientific manipulation of our physical environment. This view is shared by many of Dr. Dewey’s supporters.”

The book comes to a close with a brief section on the philosophy of Logical Analysis, which seems near and dear to Russell’s heart. Rather than fixating on intractable tasks (e.g., the business of proving or disproving God), he reaffirms the value in successive approximations towards truth - in which each stage results from an improvement, not a rejection, from what came before it. In his estimation, too many of the philosophical figures were occupied with “inharmoniously” blending the intractable ethical inquiries with disprovable theories of nature. At the time he finished the book, the conventional conception of reality had been blown asunder by Einstein and early work in quantum mechanics. In its wake, Russell saw the possibility of building entirely new systems of philosophy - and he concludes with an implicit invitation for those undaunted by the prospect.

A History of Western Philosophy is maybe the most impressive book I’ve ever read. It’s hard to believe that such breadth was credibly and coherently put together by a single mind. With each chapter, and each thinker, Russell’s clear summaries and analyses reveal a deep understanding - not only of the relevant philosophical systems, but of the corresponding historical context. It’s humbling to realize that this work was perhaps among the less impressive accomplishments by the man, when taken alongside his foundational work in mathematics, logic, and social activism.

“Do more” is my resounding takeaway.